Is Your Ideal Customer Your Actual Customer?

It’s no secret that we’re big fans of buyer personas. A buyer persona is an idealized version of your customer — a set of characteristics that most of your customers will share. Of course, people aren’t monoliths, and no one is going to exactly fit every criterion that you set out.

The idea is sound — your product isn’t for everyone, which means your messaging isn’t for everyone, either. You want to make sure that you’re talking to the right people, not wasting your time and resources trying to sell your product to people who just aren’t interested in what you have to offer.

But what happens when your buyer persona is just plain wrong? It’s more common than you might think, especially with a new company or a new product. You might think you’re creating a product for a certain person or a certain market, but you haven’t sold any yet. Once you start to move a few units, you realize that the people buying your product aren’t who you expected at all. What do you do? And how do you keep this problem from happening in the first place?

Let’s look at a few mistakes that might have pointed your buyer personas in the wrong direction.

Making Up A Buyer Persona From Nothing

When you first start out, you really don’t know who’s going to buy your product. You have an idea, of course, based on the nature of the product and the niche you’re planning to fill in the market. But you don’t really know for sure.

So you invent someone. You come up with a list of characteristics that your ideal customer has, and you start looking for — and talking to — people with those characteristics. The problem comes when you don’t adapt. Conjuring a persona from thin air has one purpose and one purpose only: getting you off the ground. Once someone starts actually buying from you, you need to adapt your persona to fit your real customers — not your perfect ones.

Only Using Qualitative Data

Gathering qualitative data is as simple as sending out surveys, and it can be useful in shaping your business — to a point. Qualitative data takes the form of non-numerical questions like:

- Tell us about yourself What was most important to you when making a decision?

- How is this product different from other products?

- Is there anything else you’d like to add?

There are two problems with relying too heavily on qualitative data. The first is that it’s hard to translate to numbers. While qualitative data can give you a useful glimpse at your customer’s motivations, fears, beliefs, and attitudes, it’s hard to assign numbers to questions like “what are your main priorities when searching for [certain products]?”

The second problem is more psychological: what people say is not the same as what they do. Users might say that they prioritize certain features, pricing, or other aspects of your business, but their actual behavioral data reflects something completely different.

Instead, start with behavioral data, lifetime value, and other purchasing habits that make a real difference toward your bottom line. Once you’ve established what your best customers do, you can send out attitudinal surveys to find out why they do it.

Using Irrelevant Data

It’s tempting to build a buyer persona into a fully fledged personality, but that’s usually not necessary. You might like picturing Dave, the sales manager who drives a Subaru Outback and goes cycling on the weekends as your ideal customer. But do those characteristics really matter?

Focus on the features of the customer that are going to make a real difference to whether they purchase your product or not:

- What are the main problems that your buyer dedicates their attention to?

- How does your buyer define success?

- What are the deal-breakers for your buyer — the main obstacles that would prevent them from purchasing?

- How does your buyer make a decision? What kind of research do they do?

- How will they finally make a purchase decision? Which aspects of a product are most important to them when deciding?

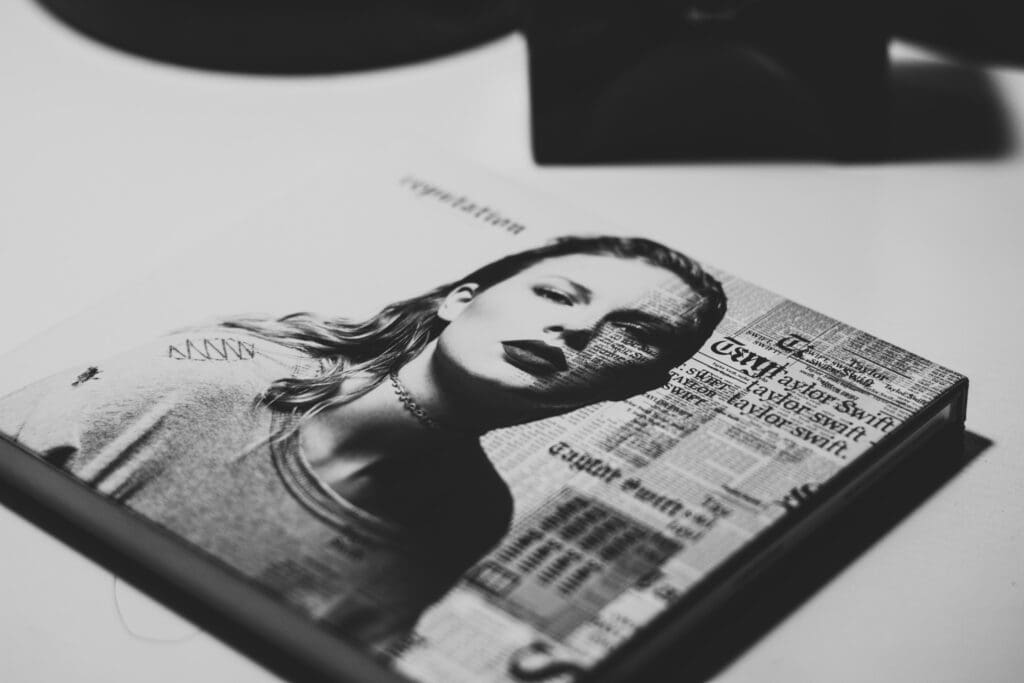

After you’ve nailed down the important parts of your buyer persona, you can speculate about what kind of magazines Dave reads and find a stock photo to fit him. In fact, assigning photographic identities to your various personas can help your team remember them better. But if you don’t have the important parts spelled out, the rest is just window dressing.

In the end, a buyer persona is as useful as the work you put into it. Too specific, and you won’t find many people who fit it. Too vague, and it won’t actually help inform your marketing efforts. Once you find a buyer persona that works for you, the benefits will become clear. But it’s worth the effort to build the right ones in the first place.